The stock market experienced a quick and severe crash on May 6, 2010, known as the Flash Crash. Within minutes, nearly $1 trillion in market value was erased before the market recovered. The financial world froze as a result. The impact of automated trading systems in hastening the sell-off and the event’s rapidity set it apart from earlier market downturns. An important indicator of the health of the stock market, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, had an intraday point decline never seen before, leaving regulators and investors scrambling to find answers.

Not only was this crash more than just a temporary hiccup in the world’s financial markets; it served as a stark reminder of the difficulties and dangers that the digital age has brought. We urgently require a more thorough comprehension of the new trading environment brought about by the transition from the open outcry system to high frequency, algorithm-driven strategies, as highlighted by the Flash Crash of 2010. To maintain market stability and investor confidence in a time where milliseconds can mean millions, it prompted a reassessment of market structure, the role of technology in trading, and how regulatory frameworks need to adapt.

The Flash Crash was significant for reasons other than its short-term monetary effects. It was a turning point for global financial markets, prompting public debate about the character of modern trading as well as investigations and regulatory reforms. Because it shows the possibilities and threats posed by automated trading and the interconnection of worldwide markets, the Flash Crash is important for traders and regulators to understand.

‘Flash Crash’: The First Market Crash in the Era of Algorithms and Automated Trading

Not only did the Flash Crash of 2010 happen so quickly and so deeply, but it also showed how automated trading and algorithms can change the way markets work, which could also make them less stable. The stock market crashed and then miraculously rose again in just a few minutes that fateful May afternoon, leaving traders and observers confused. High-frequency trading (HFT) and algorithmic strategies had been quietly changing the way financial markets worked for a while before this event brought them to the public’s attention.

As a way to make markets more efficient and liquid, automated trading systems were praised for their ability to make trades at speeds and volumes that humans could not. The Flash Crash, on the other hand, showed that these new technologies had worse sides. For example, algorithms can make market moves bigger or smaller by responding in a split second to changes in the market. Price changes that had never been seen before were made clear during the Flash Crash in 2010. This happened because of how closely these systems were linked and how quickly they were traded.

Automated trading changes more than just the mechanics of buying and selling it changes the way the market works. Whether you look at how they work or how they are regulated, it has changed everything about financial markets. Changes in the market used to be mostly caused by people making decisions based on in-depth studies of businesses and economies. Some of the signals that can set off big market events today are market data, news stories, and social media. These signals are processed by algorithms, which often cause massive and quick changes.

Since trading decisions are made in milliseconds these days, the Flash Crash also showed how hard it is to keep the market honest and stable. To better understand and run the digital marketplace, it made the point that market operators and regulatory bodies need to change. Circuit breakers, more thorough stress testing of trading algorithms, and more oversight of automated trading practices have all been used to make the market more stable since the crash.

It was a stark reminder of how technology can be both good and bad for the financial markets during the Flash Crash of 2010. Automated trading and algorithms have made things more efficient and liquid, but they have also brought about new risks and problems. It’s important to find a balance between new ideas and rules so that markets keep changing in a way that keeps them honest and lets them grow the economy.

2010 Flash Crash: Main Events

The stock market crashed very quickly and hard on May 6, 2010, and it was called the Flash Crash. Within minutes, the market lost almost $1 trillion in value. It took a while for the market to recover. This caused the financial world to freeze. Automated trading systems sped up the sell-off, and the event happened so quickly that it was different from other market downturns. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, which is a good sign of the health of the stock market, dropped points during the day in a way that had never been seen before. This made regulators and investors scramble to figure out what happened.

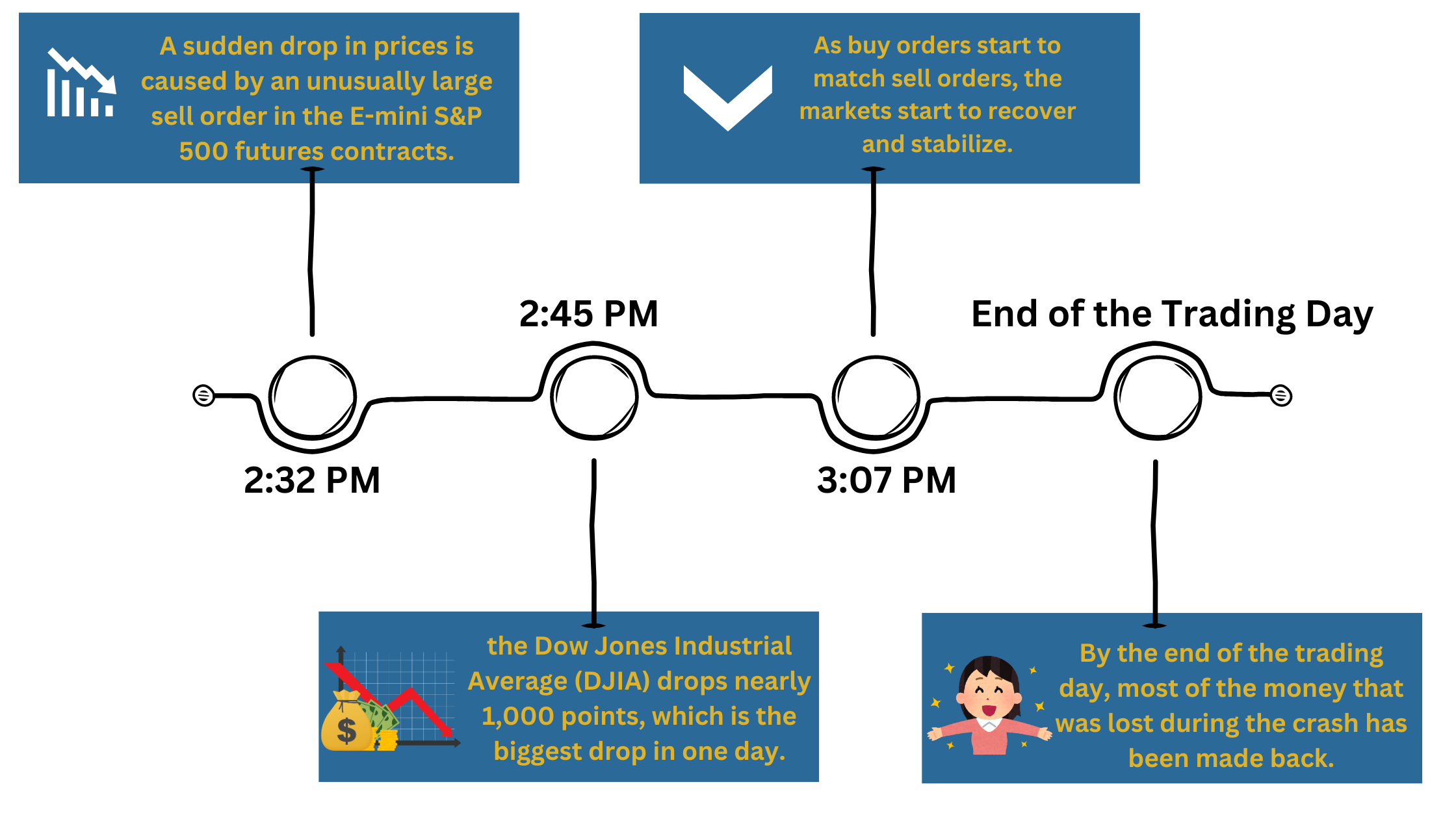

Timeline of the Flash Crash

- 2:32 PM: A sudden drop in prices is caused by an unusually large sell order in the E-mini S&P 500 futures contracts. This is the first sign of the crash. When this order comes in, high-frequency trading algorithms act quickly to carry out a lot of trades, which makes the sell-off stronger.

- 2:45 PM: the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) drops nearly 1,000 points, which is the biggest drop in one day. At that time, this was the biggest drop in one day in the stock’s history, which sent shockwaves through the financial world.

- 3:07 PM: As buy orders start to match sell orders, the markets start to recover and stabilize. The recovery is almost as quick as the drop, which shows how volatile and quickly markets can change these days.

- By the End of the Trading Day: By the end of the trading day, most of the money that was lost during the crash has been made back. The DJIA goes down 348 points at the end of the day, which is a big drop but not nearly as big as the lows of the day.

Key Statistics and Figures

- Dow Jones Industrial Average Drop: The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by almost 1,000 points at its worst.

- Recovery: The market made up most of its losses in about 25 minutes after the biggest drop.

- Role of High-Frequency Trading: High-frequency trading algorithms were very important in both speeding up the sell-off and the subsequent recovery. This shows how automated trading systems can be both good and bad.

In this infographic, the timeline and important facts from the Flash Crash are shown visually:

The 2010 Flash Crash is a stark reminder of how fragile and hard to understand today’s financial markets are. It shows how important it is to understand and control the effects of high-frequency trading and computer programs that make trades quickly. This will help keep similar things from happening again.

What Caused the Flash Crash of 2010?

People can’t say for sure what caused the Flash Crash of 2010. It was a complicated event. Instead, it was caused by a number of things coming together, with high-frequency trading (HFT) and automated sell algorithms playing a big role. Based on what was learned, here is an analysis:

Causes Leading to the Flash Crash

- Unusually Large Sell Order of E-mini S&P Contracts: An unusually large sell order of 75,000 E-mini S&P contracts, worth about $4.1 billion, was a key event that led to the crash. As a common way to keep the market running smoothly, this order wasn’t broken up into smaller amounts.

- Aggressive Selling Orders Executed by High-Frequency Algorithms: When the large sell order came in, high-frequency trading algorithms responded by carrying out aggressive sell orders. These algorithms, which are made to make trades quickly and in large amounts, made the initial sell-off much worse.

- Prevailing Negative Market Trends: The markets were already under a lot of stress from worries about Greece’s finances and the UK elections that were coming up. The markets were more likely to crash because of this unstable situation.

- Market Manipulation via Spoofing: Spoofing, a method of market manipulation, helped bring down prices. Trader Navinder Sarao was found to have caused the crash by placing orders that he didn’t plan to carry out, which threw the market off balance.

Role of High Frequency Trading (HFT)

- Exacerbation of Price Declines: During the Flash Crash, high-frequency traders made price drops worse by selling aggressively to get rid of their positions. According to the initial large sell order and the subsequent market volatility, this sell-off was a response to the fast changes in market conditions.

- Withdrawal from the Market: As the crash happened, a lot of high-frequency traders stopped trading, which had a big effect on the market’s liquidity. They were missing, which took away an important buffer that could have lessened the impact of the price drops.

- Amplification of Market Volatility: High-frequency trading, which involves quickly buying and selling contracts, made the market more volatile. The “hot-potato” effect, in which traders quickly traded contracts with each other, made the market even less stable.

With their reliance on complicated algorithms and fast trading, modern financial markets are fully susceptible to sudden and severe problems, as shown by the Flash Crash of 2010. Furthermore, it shows how important it is for regulators to keep an eye on things and create ways to stop similar things from happening again.

Who was behind the flash crash?

At first, no one knew what caused the 2010 Flash Crash, a sudden but deep drop in the price of stock index futures that surprised traders and analysts alike. But in the end, investigations led to a surprising person: Navinder Singh Sarao, a trader who worked out of his parents’ home near London’s Heathrow Airport. Sarao’s story is not only about one person’s actions, but it is also a stark example of how the connected and automated nature of modern trading can be used to cheat people.

Introduction to Navinder Singh Sarao and His Involvement

Navinder Singh Sarao, a British day trader, became one of the most important people in the story of the Flash Crash after a thorough investigation. People said that Sarao manipulated the market with complex high-frequency trading strategies. What made Sarao’s case stand out was not only how much of an effect his trading had, but also how little money he used to do it. This went against the idea that market manipulators are big, well-funded companies.

Explanation of Market Manipulation Tactics Used

There were many ways Sarao tried to trick the market, but “spoofing” was the most important. Spoofing is when a lot of orders are put in to buy or sell a security without actually doing so. This makes it look like there is a lot of interest in that security when there isn’t. Next, these orders are canceled so they don’t go through. This method tries to trick other traders and computer programs that do automated trading into moving the market in a way that helps the spoofer’s real trades.

During the Flash Crash, Sarao put in a lot of large sell orders on the E-mini S&P 500 futures contracts. This made it look like there was a huge supply, which pushed prices down. When market prices started to drop because other traders responded to his fake orders, Sarao would cancel the big sell orders and execute real sell orders at the higher prices, making money from the price changes that were caused by him. This manipulation made the market much more volatile on May 6, 2010, which made the market’s quick drop even worse.

These strategies Sarao used showed holes in the market’s structure and how hard it is to find and stop these kinds of manipulative actions in real time. Sarao’s activities went unnoticed for years, which shows how sophisticated his methods were and how hard it is for regulators to keep an eye on and control high-frequency trading.

Navinder Singh Sarao’s role in the Flash Crash should serve as a warning about how the market can be manipulated in a time when algorithmic and high frequency trading firms are the norm. More attention was paid to high-frequency trading, and steps were taken to stop similar events from happening again. For example, market surveillance was stepped up, and rules against spoofing were put in place.

How Flash Crashes Work

Some of the most dramatic and unsettling things that can happen in the financial markets are flash crashes, in which the prices of assets drop and then rise very quickly, sometimes within minutes. It is important to understand how these things happen, as well as the role of high-frequency traders (HFTs) and market liquidity, if you want to fully understand how complicated modern financial markets are.

Mechanics Behind Flash Crashes

- Rapid Price Movements: A flash crash is characterized by a sharp drop in the prices of assets that is followed by an equally quick rise in prices. This trend is mostly caused by the digital age of trading, where computers and algorithms make a lot of trades very quickly, faster than human traders could ever imagine.

- Trigger Events: A trigger event, such as a big trade, important news, or even a technical glitch, can set off a flash crash. When this event happens, it sets off a wave of selling or buying interest that is picked up by automated trading systems.

- Algorithmic Amplification: Many trading algorithms are programmed to either follow trends (trend-following algorithms) or close positions at certain loss levels (stop-loss orders). When these algorithms notice the first movement, they might make trades automatically that strengthen the trend, which makes the price move much faster.

- Liquidity Vacuum: As prices change quickly, liquidity can quickly disappear. Liquidity is the ability to buy or sell an asset without making the price change significantly. There may be less liquidity in the market if high-frequency traders stop placing orders to buy and sell all the time. This could make the liquidity crisis worse.

Role of High-Frequency Traders and Market Liquidity

- Providers of Liquidity: High-frequency traders help the market have liquidity by placing a lot of orders very quickly. When everything is normal, this activity helps make sure that there is always a buyer for every seller and a seller for every buyer. This keeps markets working well and prices stable.

- Withdrawal During Volatility: However, high-frequency traders may quickly change their strategies, cancel existing orders, and not place any new ones during times of extreme volatility. Part of this behavior is a defense against losing a lot of money because the market is so unpredictable.

- Impact on Flash Crashes: The exit of high-frequency traders during a flash crash creates a “liquidity vacuum,” where sellers can’t find many or any buyers at the expected price levels. This can cause prices to drop significantly. As soon as the market starts to feel more stable, these traders may come back in. This will help restore liquidity and speed up the price recovery.

There are two sides to high-frequency trading, and flash crashes show how much modern markets depend on algorithmic and automated trading systems. Even though these technologies have made financial markets more efficient and liquid, they also make them more vulnerable in new ways, such as by allowing prices to change quickly and significantly. It is important for regulators, market participants, investors, and observers to understand these dynamics as they try to make sense of the complicated financial world we live in today.

Preventing a Flash Crash

To regulatory agencies and stock exchanges around the world, the Flash Crash of 2010 was a harsh wake-up call that made it clear that steps needed to be taken to stop similar sudden market crashes in the future. Several tools, such as circuit breakers and trading curbs, were created or improved in response to improve the stability and honesty of the market. Aiming to provide a safety net during times of extreme volatility, these steps will lessen the effects of possible flash crashes.

Measures Taken by Regulatory Agencies and Stock Exchanges

Major stock exchanges and regulatory bodies like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) looked closely at market structures and trading protocols after the Flash Crash. Their goal was to find weaknesses and carry out plans to stop similar things from happening. The measures that were approved are:

- Enhanced Surveillance and Oversight: Regulatory agencies spied on market activities more closely, using more advanced technology to spot odd trading patterns or dishonest actions in real time.

- Stricter Rules on Algorithmic Trading: Rules were tightened on the use of trading algorithms, forcing companies to put in place risk controls and make sure that their trading systems don’t cause market instability by accident.

- Market Maker Obligations: To keep the market liquid during times of stress, specific market makers were given clearer roles and duties, such as giving throughout the trading day buy and sell quotes.

Introduction of Circuit Breakers and Trading Curbs

Implementing and improving market-wide and security-specific circuit breakers, along with other trading volume limits, was one of the most important responses to the Flash Crash.

- Market-Wide Circuit Breakers: In the event that major indices like the S&P 500 experience a significant drop from their previous day’s closing price, these circuit breakers are designed to stop trading across all markets for a set amount of time. For example, 7%, 13%, and 20% drops are set as thresholds for these halts. The length of the halt increases with the severity of the drop.

- Security-Specific Circuit Breakers:The security-specific circuit breakers, which are also called Limit Up-Limit Down (LULD) mechanisms, stop individual stocks and ETFs from trading outside of certain price ranges. If the price of a security moves too quickly outside of these bands, trading stops. This gives market participants time to look at their positions and provides more liquidity.

- Trading Curbs: In times of high volatility, trading in a certain security or market is temporarily limited during trading curbs, also known as “cooling off” periods. Temporary limits on short selling or the installation of stricter market-wide circuit breakers are two examples of this.

Following the Flash Crash of 2010, regulatory agencies and stock exchanges have continued to work to protect the financial markets from sudden and severe volatility. Although these systems have been tested and improved over the years, it is still hard to find the right balance between market freedom and efficiency and the need for stability and protection against systemic risks. As the financial markets change, especially as technology and automated trading become more important, these avoidance strategies will have to change to deal with new threats and weaknesses.

How long did the 2010 flash crash last?

The 2010 Flash Crash on May 6 is notorious not only for the depth of its impact but also for the astonishing speed of the market’s decline and subsequent recovery. The entire event unfolded and reversed within an incredibly short period, showcasing the extreme volatility that can occur in modern electronic markets.

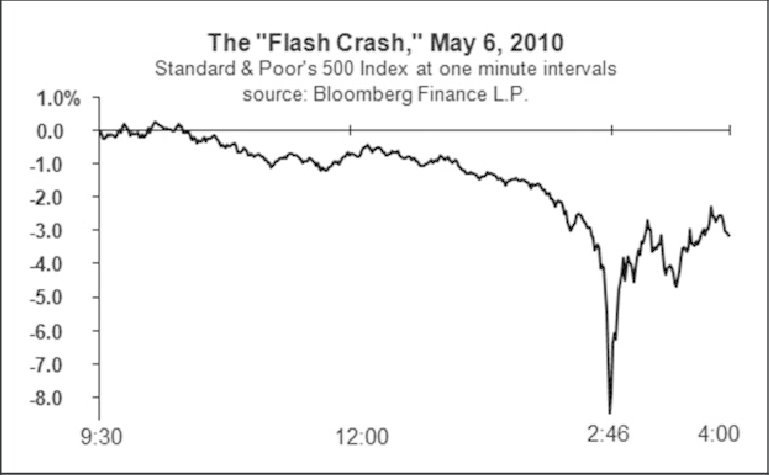

Specific Duration of the Crash

The most intense period of the Flash Crash lasted approximately 36 minutes. The rapid sell-off began around 2:42 p.m. EDT, with the market hitting its lowest point at about 2:47 p.m. EDT. By 3:07 p.m. EDT that same day, the markets had remarkably recovered most of the losses. During this brief window, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) plummeted nearly 1,000 points, marking the largest intraday point decline in its history at that time.

Discussion on the Rapid Recovery Seen After the Crash

The rapid recovery seen after the Flash Crash is as notable as the crash itself. Several factors contributed to this quick rebound:

- Circuit Breakers and Trading Halts: The activation of circuit breakers and trading halts in response to the crash provided a cooling-off period. These mechanisms temporarily stopped trading, allowing for a reassessment of positions and a calming of market panic. When trading resumed, it did so more orderly, contributing to the stabilization of prices.

- Automatic Buy Orders: Many traders and automated systems had set buy orders at lower prices as a strategy to purchase stocks at a discount in case of a market dip. When the prices fell rapidly during the Flash Crash, these buy orders were triggered en masse, injecting buying pressure into the market and aiding in the recovery.

- Market Corrections: The initial sell-off was driven by a combination of human error and algorithmic trading responses to market conditions, rather than a fundamental change in the economic outlook. As market participants recognized this, confidence was restored, and the market corrected itself from the overreaction.

- Regulatory Intervention: The SEC and other regulatory bodies closely monitored the situation, and their readiness to intervene may have reassured market participants. In some cases, trades that occurred at absurdly low prices were canceled, rectifying some of the most egregious anomalies from the crash.

The Flash Crash of 2010 underscored the susceptibility of modern markets to sudden and sharp movements, largely driven by automated trading systems reacting to each other and to news or events, rather than more than half by human decision-making. The event led to significant changes in market regulations and trading practices, aiming to prevent such drastic fluctuations in the future. Despite the fleeting nature of the crash, its lessons continue to inform the strategies used by exchanges, regulators, and traders to safeguard against similar incidents.

Other Flash Crashes

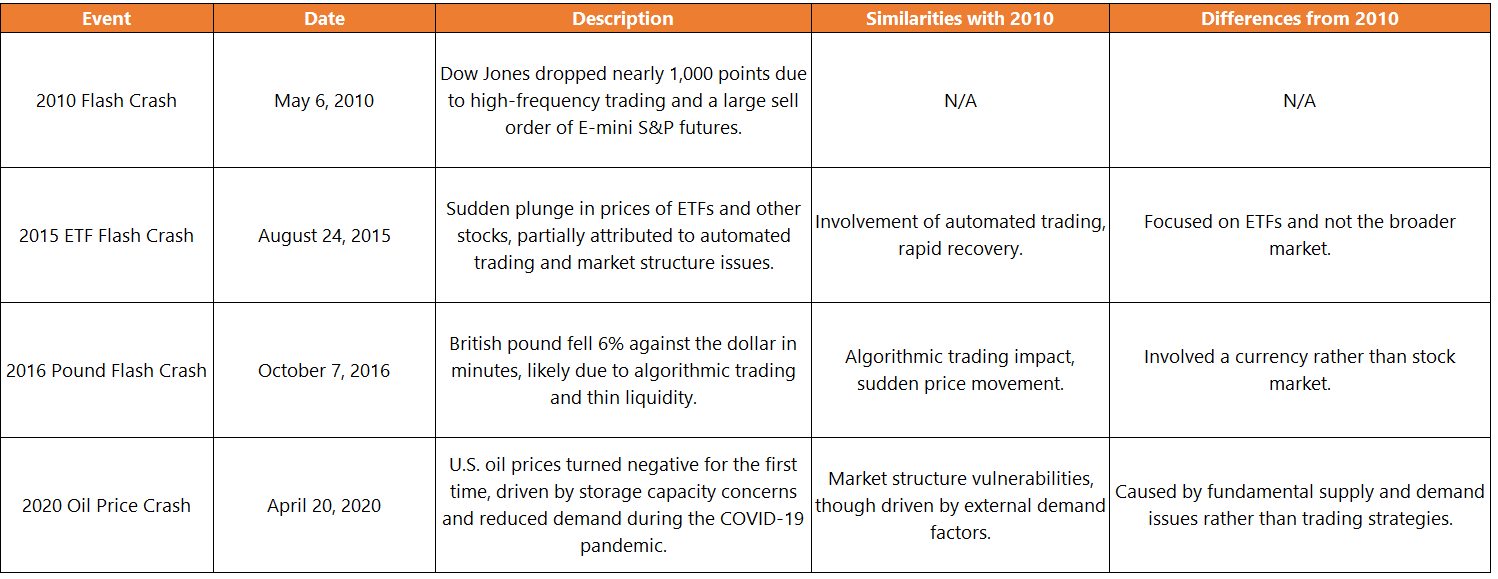

Here’s a comparison of the 2010 Flash Crash with other notable flash crashes in history, highlighting both similarities and differences:

This table illustrates that while the mechanism of a flash crash can vary—impacting stock indices, ETFs, currencies, or commodities—the role of automated trading and market structure vulnerabilities are common threads. Each event also showcases different triggers, from algorithmic trading to fundamental economic factors, underscoring the multifaceted nature of financial markets’ risks.

FAQs

What is a Flash Crash?

A flash crash refers to a very rapid, deep, and volatile fall in security prices within an extremely short time frame, often just a few minutes, followed by a quick recovery to more stable levels. These events are characterized by their suddenness unusually high volatility, and the significant recovery that follows.

What Triggers a Flash Crash?

Flash crashes can be triggered by a variety of factors, including large sell orders, significant news events, technical glitches, or the rapid reaction of high-frequency trading (HFT) algorithms to market conditions. Often, it’s not a single factor but a combination that leads to a flash crash.

Can Flash Crashes Be Prevented?

While it’s challenging to entirely prevent flash crashes due to the complex and interconnected nature of financial markets, regulatory agencies and stock exchanges have implemented measures such as circuit breakers, trading curbs, and enhanced oversight of algorithmic trading to mitigate their impact and frequency.

How Do Circuit Breakers Work?

Circuit breakers are automatic mechanisms that temporarily halt trading on an exchange if prices hit predefined levels within a trading day. They are designed to provide a pause during which investors can gather information and make rational decisions, thereby reducing panic-selling.

What Role Does High-Frequency Trading Play in Flash Crashes?

High-frequency trading (HFT) can both contribute to and mitigate the effects of flash crashes. On one hand, HFT can amplify price movements due to the speed and volume of trades executed. On the other hand, HFT can also provide liquidity and aid in the market’s recovery.

Have There Been Other Notable Flash Crashes?

Yes, there have been several other flash crashes since 2010, affecting various markets and assets, including equities, currencies, and commodities. Each event has its unique triggers and characteristics but often shares similarities such as the role of automated trading and rapid price movements.

What Was the Impact of the 2010 Flash Crash?

The 2010 Flash Crash had a significant short-term impact on the market, erasing nearly $1 trillion in market value within minutes. Although the market largely recovered by the end of the trading day, the event led to increased regulatory scrutiny, changes in trading rules, and a greater focus on the stability of financial markets.

Are Flash Crashes a Risk to Individual Investors?

Flash crashes primarily pose a risk to investors who are trading actively or have stop-loss orders in place, as they may execute at undesirable prices during the volatility. Long-term investors are generally less affected, especially if the market recovers quickly.